Florida now reports only extreme cases, causing a 20% drop in cases, while pushing for a systemic interpretation of homelessness

By Katie Aulenbacher

Mental illness and substance abuse are likely more prevalent in Florida’s homeless community than official reports lead organizations and the public to believe.

In 2017, the Florida Council on Homelessness — a state government council that “develop[s] policies and recommendations to reduce homelessness,” according to their website — increased the requirements necessary to be considered mentally ill in their reports, without public explanation. This led to a 20% drop in cases, a possibly misleading drop as it shifts focus to only chronic or severe cases rather than all cases, and could create a wide ripple effect impacting policy, funding, and outreach decisions.

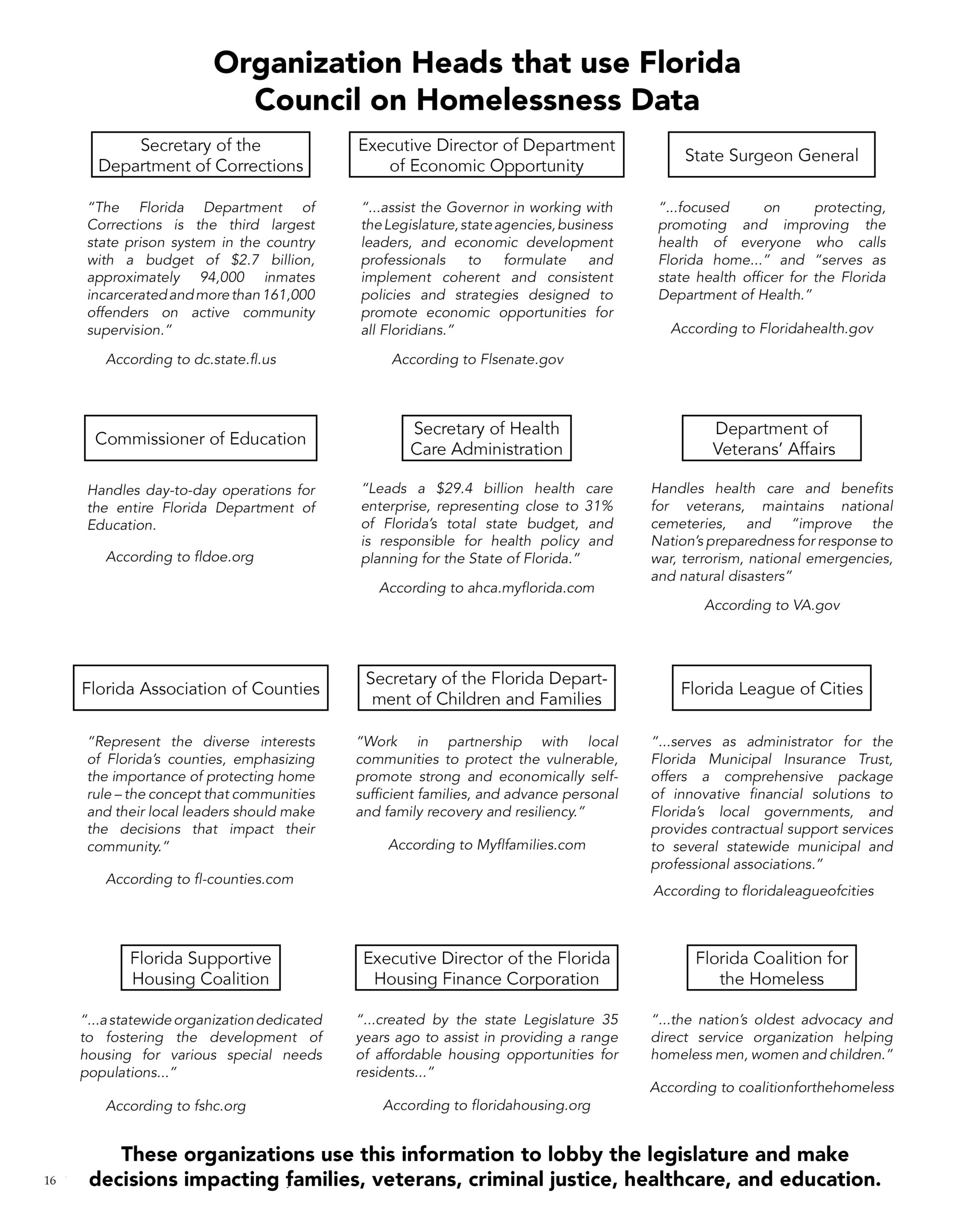

The Florida governor, the State Surgeon General, the Executive Director of Veterans’ Affairs, and the Commissioner of Education are only some of the organization heads that use this data to lobby the legislature and make decisions impacting families, veterans, criminal justice, healthcare, and education.

In Florida, the shift from reporting total incidence of mental illness and substance abuse in 2016 to only chronic or severe cases in 2017 led to this 20% drop. The 2016 report found that 33.2% of homeless individuals were suffering from substance abuse and 34.2% from mental illness, while in 2017 those numbers were 13.3% and 14.8%, respectively. For comparison, a 2001 Urban Institute brief noted that “only one in four homeless adults did not report any mental health or substance abuse problems during the past year.”

Rick Butler, Vice Mayor of Pinellas Park, Treasurer of the Florida State Homeless Leadership Board, and member of the Council on Homelessness commented, “You see, we don’t gather the data. We just sit there and listen to what they’re reporting to us. All we can do is sit there and hope everything that they’re telling us is the right information…To me, number-wise, that percentage drop doesn’t make sense.”

To the best of Florida Council on Homelessness Chairperson Shannon Nazworth’s recollection, the switch to reporting only extreme cases reflected an attempt to align with the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) reporting guidelines. HUD oversees federal housing initiatives including the annual point-in-time (PIT) count of homeless persons.

“I do believe that was around the time that HUD kind of started changing different things that were required. And, so, the Council and Office on Homelessness, really it was the Office on Homelessness that shifted its reporting requirements and other things to align with the HUD requirements, trying to streamline the reporting requirements on the CoC’s [Continuums of Care, the local organizations that facilitate PIT counts],” Nazworth said.

A similar attempt to align with federal guidelines in California led to a dramatic underreporting of the prevalence of mental illness and substance abuse in Los Angeles’ homeless community, according to the LA Times. Using the same raw data as the city, LA Times found that 67% of unsheltered individuals suffered from mental illness or a substance abuse disorder, while the city reported a figure of only 29%. In their own words, the Times’ reporting raised “questions about whether government officials are taking the right approach and doing enough for people on the street who have little hope of getting into housing anytime soon.”

“It’s like, the question is, ‘Do you feel like you have a mental illness.’ The guy’s looking at me like, ‘Not if I have another beer, I don’t!’ That’s the reality of what you’re dealing with out there,”

One expert interviewed by the Times, Executive Director of the California Policy Lab at UCLA Janey Rountree, said, “There really needs to be an examination of the inflow of the unsheltered population, and are there issues of access to medical care, mental health care and to substance abuse treatment that are just as important as thinking about how to house them immediately when they do become homeless.”

Asked if the design of the PIT count, when volunteers go out and individually count the unsheltered homeless, could lead to undercounting important cases, Butler said, “Absolutely. Yeah. I think most of the time, the sad part about it is [if] they don’t answer truthfully, they don’t get any follow up help. So I think a lot of people are just too embarrassed to say, ‘Yeah, I’ve got a problem. I need to get some help.’ I could absolutely see it being undercounted.”

This amounts to the statistic of mental illness and substance abuse being wholly self-reported by those possibly with these ailments.

“Let’s be honest, we take one day a year to go out and count our homeless. Does that even sound right? But that’s all that we can go on,” continues Butler. “There are some people that we can’t get to…Given what HUD guidelines are, as in, ‘You will do this, and here are the questions that you will ask, no matter how stupid they are,’ and you’re dealing with sometimes sitting in the middle of the woods with five or six people in the middle of a rainstorm trying to ask questions and trying to get straight answers. And it’s a very hard thing if you track that…I’ve been out there a few times.”

The HUD guidelines state that in order to be counted as substance misuse disorder or a serious mental illness, a case must meet three conditions:

1. Seriously limit an individual’s ability to live independently

2. Be for a long-continuing or indefinite duration

3. Could be improved by the provision of more suitable housing conditions.

This means if someone doesn’t report that their condition prevents them from “holding a job or living in stable housing,” their case goes uncounted.

“It’s like, the question is, ‘Do you feel like you have a mental illness.’ The guy’s looking at me like, ‘Not if I have another beer, I don’t!’ That’s the reality of what you’re dealing with out there,” Butler said. “The ones that are [obviously struggling] are like, ‘Oh no, there’s nothing wrong with me. I’m fine.’ But you have to mark down what was said…It’s an antiquated system to get that type of information, that’s required by HUD…Is the data correct? Maybe 60%, 65%, 70%. But there is going to be flaws in the system.”

Asked if the Council’s policy recommendations would change if the data gathered were different, Nazworth commented that “policy recommendations are based on the data available, so if the data changes, and there was an uptick in one group or another, we would definitely look at what are things we could try to do to address that.”

Crisis counselor and director of New York’s Neighborhood Coalition for Shelter Jeff Grunberg, when asked if this change in definition of mental illness could affect funding, said, “absolutely.”

“If the government’s going to fund a substance abuse division, that division has to set up their parameters, who is worthy of their treatments…” Grunberg continued. “That division is going to fund local programs. The local programs are told, ‘We’re going to give you 150k, you have to serve 35 addicts, here’s the definition…’ The funding stream dictates who gets treated. Of course, what becomes the funding stream is dictated by lobbying and advocates.”

He further explained that focusing on specific ailments “does help you lobby for particular funding to bolster your outreach efforts to hopefully succeed in getting someone indoors who otherwise might not come indoors without that focus,” concluding that statistical changes resulting from definitional changes “will affect lobbying.”

“It is a public document,” said Nazworth, referring to the Florida Council on Homelessness’ annual report. “…and of course [stakeholder groups] can use it to advocate with the legislature or others on best practices and, of course, legislative recommendations as are outlined in the report.”

Grunberg described a personal example of a negative byproduct of altering mental health definitions that took place three decades ago, while he was running a treatment program at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center. According to Grunberg, the Commissioner of the New York State Office of Mental Health redefined the segment of the population the department was responsible for helping saying, “he changed the definitions of who could be considered severely mentally ill. Now suddenly, his agency was only responsible for taking care of a smaller number of people.”

As a result, “a lot of people didn’t meet the criteria necessary to be called functionally disabled, therefore they didn’t qualify to be in my program…There were a lot of people who were absolutely disabled, but weren’t ‘crazy’ enough.”

Alongside the transition to tabulating only more extreme cases, Nazworth shared that the Council has mirrored HUD’s emphasis on a systemic understanding of homelessness. “The shift to focusing on systemic causes is because, in the end, this is a systems issue. It’s a systems failure issue. People are not homeless because of individual choices they made and decisions they made…And we’re just trying to help people understand, with systems issues we can change systems and align systems better so that we can better address homelessness. And I do think that’s what HUD was trying to do with its shifts as well, is look at the systemic level things that you can influence, and help incentivize best practices to help reduce the number of people who are homeless on our streets.”

Butler expressed doubts that overly powerful systems could be the solutions to the problems they create saying, “It is frustrating. I know I’ve been on [the receiving end of HUD guidance] I don’t know how many years, and I kind of chuckle every time, like, ‘This is so ridiculous.’ But you ain’t going to change it. You ain’t changing it. The whole system is the system, and the system says this is what you need to do.”

“The shift to focusing on systemic causes is because, in the end, this is a systems issue. It’s a systems failure issue. People are not homeless because of individual choices they made and decisions they made…”

As a result of this shift to a systemic understanding of homelessness, the Council’s annual reports have gradually transitioned from a more neutral characterization of the causes of homelessness, as a combination of individual and societal factors, to accentuating the societal factors.

For example, the 2015 report stated, “There are a host of issues that may lead to homelessness including job loss, family crisis, disabilities, and struggles with mental health and substance abuse,” while in 2019, the report reads, “The systemic causes of homelessness are, however, often overlooked while personal issues tend to be overemphasized…For elected officials, policymakers, and planners, it is especially critical to recognize the societal and systemic issues that contribute to homelessness.” There is no source cited for the claim that individual factors are overemphasized at the expense of systemic causes.

The 2019 report includes the further uncited claim that “mental health issues and substance abuse do not directly cause [homelessness],” in apparent contradiction of the HUD surveys, which require individuals to state a causal connection between their mental health and substance issues and their homelessness in order for their condition to be counted.

When asked about the basis for that claim, Nazworth responded, “Well there is no data to say that they directly cause homelessness. There are people with mental health and substance use issues who are not homeless. Again, I don’t know of any data that directly says that that is a cause. It may be an exacerbation to a challenge. It may make things more challenging for certain individuals, but it’s not the reason they’re homeless. If that were the case, then all people with serious substance use issues would be homeless, and that’s just not the situation.”

This is in contrast to Grunberg’s experience, where the vast majority of people explain their homelessness in terms of personal decisions: “They disagree with their own advocates. Imagine that. Advocates disagree with the homeless people they’re advocating for. We asked the homeless who they blame. We found that…70% blame themselves…The homeless are Americans too. They believe in bootstrapping–’lift yourself up by your bootstraps’–they want to work.”

Nazworth continued by saying that “part of it is to help policymakers who are not directly involved with homelessness and don’t live in this space the way the rest of us do on this Council and others understand that while there may be exacerbating issues and it may cause more challenges, it isn’t the reason. It may contribute to the cause, but it’s not the reason that the person is homeless.”

An earlier report endorsed legislation aimed at improving mental health and substance misuse treatment facilities in order to “address two major contributing factors for homelessness,” Grunberg commented. “It is very touchy, very important, how we label ‘why.’ We should not soft-sell this. Having mental illness and being homeless is a one-two punch.”

The 2019 report also includes the claim that “the majority of people who become homeless do not have behavioral health issues.” Nazworth, when asked if this could be misleading, since only more extreme cases were tabulated, said, “I don’t think so. We were trying to highlight that most people when they think of homelessness think only of chronic homelessness, and homelessness is a much broader group of individuals in our community.”

She clarified that while “there is obviously some correlation between mental health and substance use and homelessness, whether one is exacerbated by the other, chicken and egg scenarios, I don’t know that there’s real good research on that aspect of it, but most people don’t have a chronic behavioral health issue.”

Nazworth also stressed that the goal of de-emphasizing mental illness and substance abuse in the reports was to educate policymakers that homelessness comes in all shapes and sizes saying, “Homelessness is about all homeless individuals. School kids right through to the persons with the greatest demons that we’re all striving to help.”

Jeff Branch, Legislative Advocate for member organization Florida League of Cities, commented, “There’s a whole host of factors that may cause people to become homeless. I would just speak very broadly that no report should overlook all the different contributing factors of homelessness, whether it’s caused by individual actions or external factors that they have no control over. Our focus is how do you end it, and how do you prevent it.”