By Robert Davis

Local housing experts are concerned that Florida could see a significant spike in homelessness in 2023 after a year that saw hurricanes Ian and Nicole ravage the state’s southern peninsula and destroyed affordable homes for some of the state’s lowest income earners.

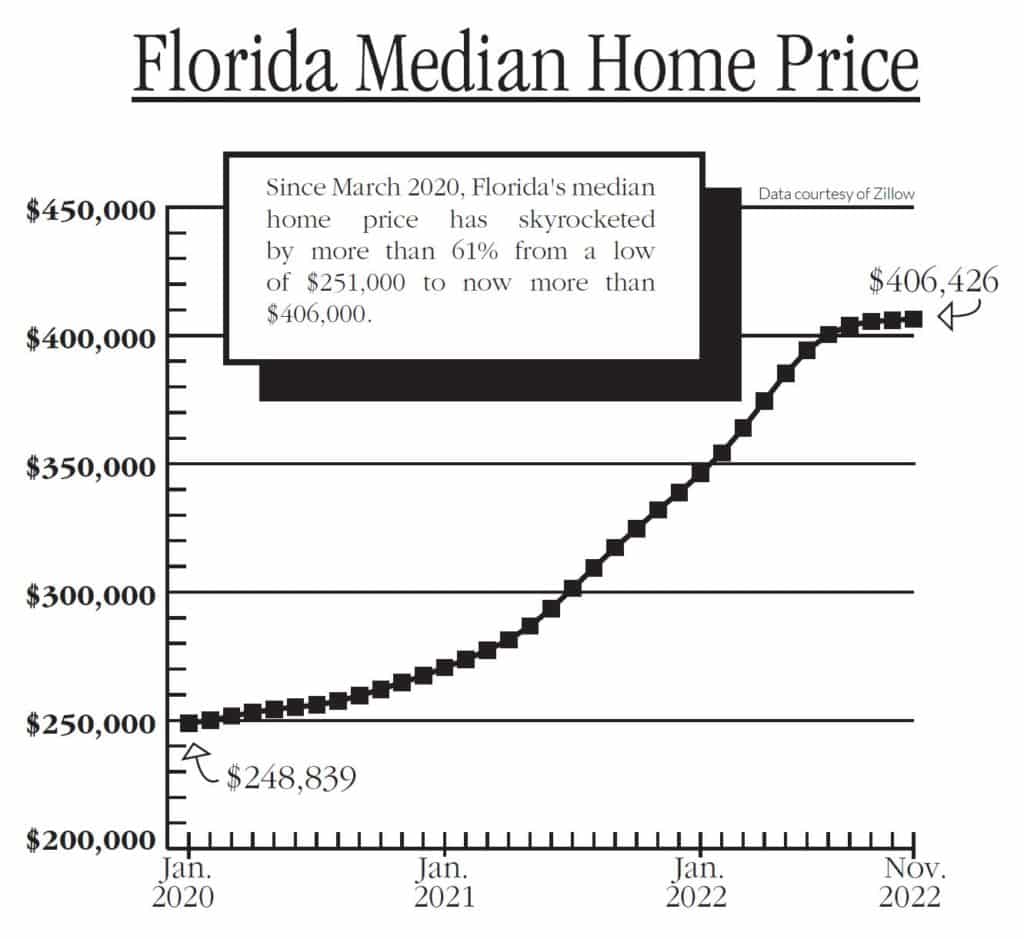

Florida has been one of the hottest housing markets in the US since the pandemic began in March 2020. In nearly three years, the state’s median home price has skyrocketed by more than 61% from a low of $251,000 to now more than $406,000, according to data from Zillow. Meanwhile, data from the Florida Housing Coalition shows that the state leads the country with more than 53% of renters being housing burdened, meaning they pay 30% or more of their monthly income on rent and utility expenses, because of rent increases and stubborn inflation.

As the calendar turns to the new year, some experts are concerned that these conditions will cause homelessness to increase if the state does not intervene.

“There was already a gap between what housing costs and what people can afford,” Anne Ray, a researcher at the Shimberg Center for Housing Studies at the University of Florida, told the New York Times in October after Ian made landfall.

“The communities that were hardest hit in Southwest Florida already had been seeing large increases in rent over the past year or so,” Ray continued. “A storm like this comes along and we could lose that critical supply of affordable housing.”

How big is the problem?

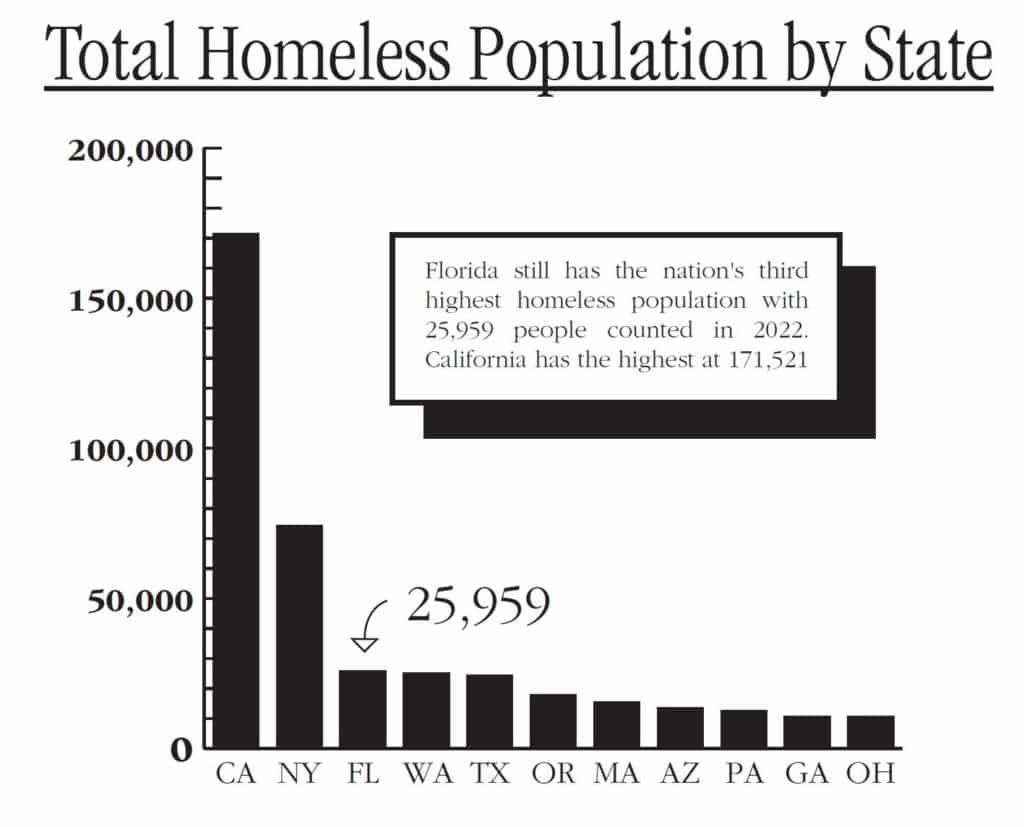

Florida has made a lot of progress on providing housing and services for people experiencing homelessness in the state. The state has seen its homeless population decrease by 41%, or more than 13,000 people since 2007, according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s 2022 Homelessness Assessment Report, which compiles state level one-night count data.

The one-night count, also known as the “Point in Time Count,” typically occurs in late January and is designed to be a snapshot of homelessness in a local area. Totals can vary widely between counts because it relies on volunteers to find homeless people during one of the coldest months of the year and requires homeless people who are contacted to identify themselves as homeless.

As this paper has previously reported, some people avoid identifying themselves as homeless because of the stigma that is attached to homelessness.

“It takes significant time, effort and building trusted relationships between a client and a case manager to work towards permanent housing solutions,” Therese Everly, executive director of the Lee County Homeless Coalition, told Naples Daily News in May.

The data collected during the one-night counts are then used to determine the amount of federal funding that cities receive to address homelessness. However, some say the data collected during the 2022 count is unreliable because HUD, which oversees the Point in Time Count, did not require local Continuums of Care to conduct unsheltered counts because of the pandemic. Continuums of Care are nonprofit agencies that partner with HUD to deploy homeless resolution programs across the country.

What is causing homelessness to increase in Florida?

Despite Florida’s progress on homelessness, the state still has the nation’s third highest homeless population with 25,959 people being counted in 2022. At the same time, there are signs that Florida’s housing market could leave many cost-burdened households behind.

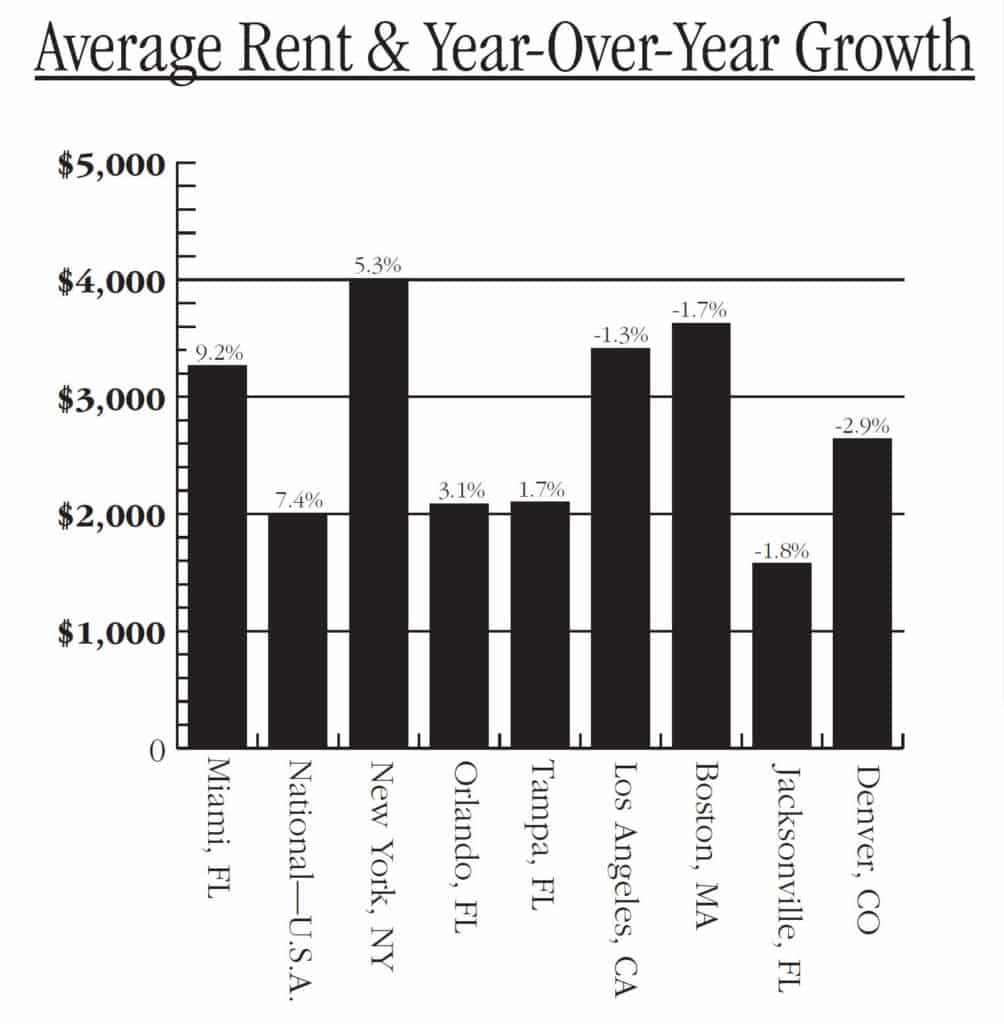

One issue is that rents in many cities in Florida are rising at a time when wages in the state are falling because of inflation. Tampa, Miami and Orlando all saw their rents increase in November, according to Redfin’s rent tracker. Miami led the way with a 9.2% growth rate year-over-year with an average rent of more than $3,200 per month. Tampa and Orlando saw their rents grow by 1.7% and 3.1% and both cities have an average rent of nearly $2,100 per month, Redfin’s data shows.

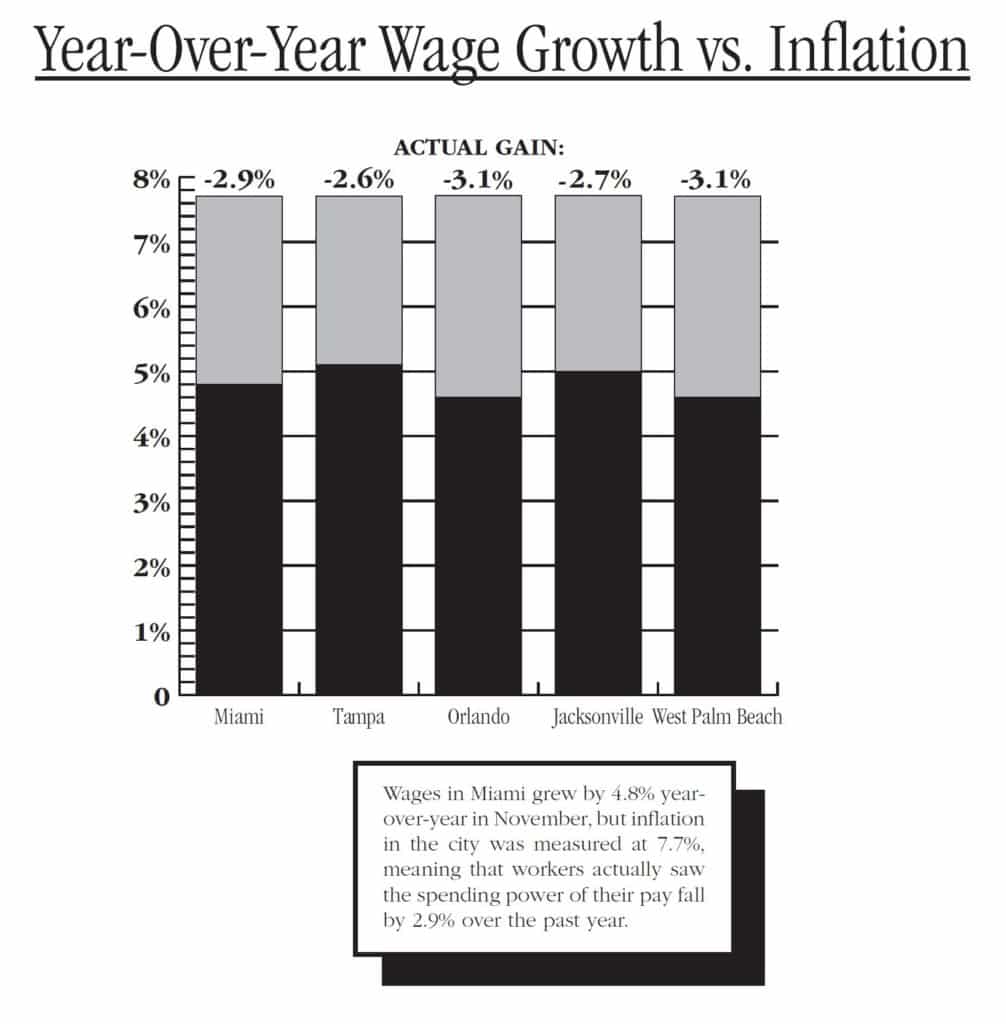

Wages in each of these cities have not been able to keep up with these rent increases either, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. For example, wages in Miami grew by 4.8% year-over-year in November, but inflation in the city was measured at 7.7%, meaning that workers actually saw the spending power of their pay fall by 2.9% over the past year.

But this hasn’t stopped people from needing housing, and that demand for housing is being squeezed by historically low supply of homes while natural disasters like hurricanes Ian and Nicole wiped out more homes. That’s one reason why the median home price in Florida has grown by 10% to $390,000 over the last year, as of November, according to Redfin.

“Because of COVID, because of the rental crisis that’s going on in our community, because of migrant inflow, we’re seeing tremendous new demands that we haven’t seen before,” Victoria Mallette, executive director at Miami-Dade County Homeless Trust, told the Miami Herald.

The rising housing prices have also coincided with an increasing number of households facing eviction. Meanwhile, data from the Census Bureau’s latest Household Pulse Survey shows that more than 109,000 renters in Florida feel they are “very likely” to be evicted within the next two months, up from just 13,000 households who said they would face an eviction in November 2021.

These factors have caused local leaders, like Democrat Rep. Val Demmings, to call for more protections for Florida’s low-income renters.

“We can’t let Florida families lose their homes due to emergencies outside of their control,” Demmings said in a press release.

What’s being done to make housing more affordable in Florida?

Several cities across Florida have budgeted millions of dollars to preserve and create affordable housing within their jurisdictions, but the efforts may be too little too late.

For instance, Palm Beach voters recently approved a $200 million ballot measure to create 20,000 affordable homes over the next 10 years. But that is only half of what is needed to provide affordable housing to the more than 51,000 extremely cost burdened households in Palm Beach County, according to a housing needs assessment conducted by Florida International University in 2020. These households pay more than half of their monthly income on housing and utility costs.

“It’s staggering, the increase that we’ve been seeing. But it’s also tied to supply and demand,” Kevin Kent, a local realtor, told WPBF in April. “There is very, very little supply and there is a huge demand for our area and that continues to push pricing both on rentals and on sales and purchases.”

For some experts, solving homelessness comes down to a simple choice: Do local leaders care enough about the problem to put forward solutions, or not?

“It’s not that we can’t solve these issues, it’s that we won’t,” Justin Barfield, outreach and development director of Capital City Youth Services, told the Tallahassee Democrat.