Out West is vast stretches of public land, used by farmers, tourists, and sometimes the homeless

By Channing Kaiser and Andrew Fraieli

In 2017, I lived out of my car for three months. I stayed almost exclusively on public lands, making the occasional exception for Walmart parking lots when necessary.

One evening, I camped off a National Forest road near Mt. Rainier in Washington State. I thought I had the spot to myself and was surprised when a sedan pulled up near me in the settling darkness. A mother and her two children got out to admire the brook, and then crammed back inside to sleep. They had no tent.

It was at that moment I realized how different our circumstances were. Me, a lone female camping in the woods for recreation, and them — whatever their story was — taking refuge in the woods for a reason beyond leisure.

Public lands have always been a source of refuge. When Europeans came to America seeking freedom from oppression, the idea of open land was a symbol of that refuge, and an idea that has progressed through time. With that, many types of people have sought that refuge and freedom in the United States’ public lands for decades, finding home there — including those who aren’t camping for leisure or escapism, but because of housing insecurity.

But these public lands are not meant to be habited, by lack of design and capability. The long-term stays of people present the clashing challenges to federal agencies of both supporting the unsheltered individuals who have nowhere else to go, and maintaining the integrity of the land — burdening the unhoused with restrictions when they are there from necessity.

In general these people are not camping on public lands because they are choosing to be intentionally nomadic, but because they lack the resources to maintain a more conventional ‘homed’ lifestyle,

Currently, the majority of federal land is managed by the United States Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) who, together, oversee a total of over 400 million acres — an area more than twice the size of Texas.

Within and because of this vast and difficult terrain, a lack of agency resources, and seasonal fluctuations, there is no available number for how many non-recreational long-term campers are staying on public lands at any given time. They are simply too hard to count. But the types of people staying are not a mystery, making the discussion broader than just what comes to mind with the term “homeless,” as it does not adequately describe all those individuals living on public lands.

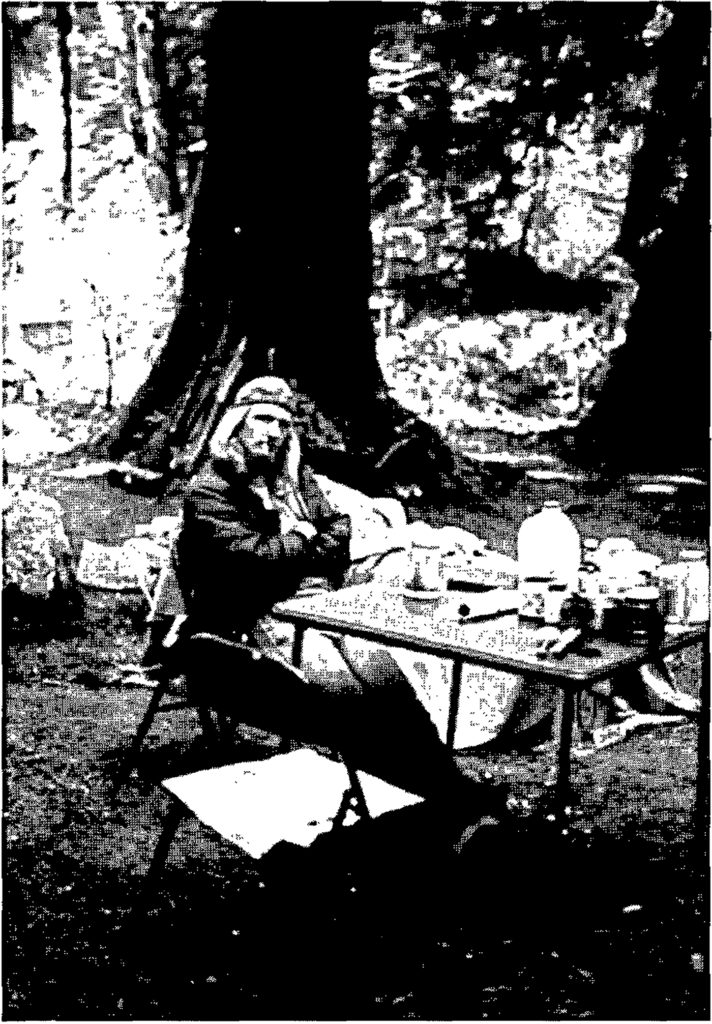

Non-recreational long-term campers can be divided into three groups: economic refugees, separatists and voluntary nomads — each with their own motivations, habits and effects on the land. These distinctions were created by Dee Southard, an ethnographic researcher who spent 18 months on rural public lands in Oregon, following and interviewing over 300 wilderness residents over six years.

These categories encompass everyone from retirees who live out of their trailers, to those fleeing domestic violence, to nomads who simply want to be away from the world, with economic refugees being those experiencing homelessness in the traditional sense.

“In general these people are not camping on public lands because they are choosing to be intentionally nomadic, but because they lack the resources to maintain a more conventional ‘homed’ lifestyle,” said Southard in her 1997 study. “They are generally not happy with the fact that they are homeless…almost all the non-recreational homeless campers are living in extreme poverty.”

A major complaint that Southard heard from recreational managers from BLM and USFS about these people was that they “do not really know about how to camp ‘lightly’ in the woods,” pointing to them not knowing how to “properly dispose of their excrement, waste water, or trash.”

This study may be from 1997, but the points still hold true today, with people still finding refuge in these lands, and the BLM and USFS still trying to find them. “Just about every place has some story of a guy living out in the woods who we can never find,” Chris Boehm, the USFS assistant director of law enforcement, told Vice in 2016. “Our officers know the places to look, but some people are really good at hiding.”

Much of the hiding and frequent movements of those suffering from homelessness and living in the forest are because of USFS and BLM camping regulations, as well as enforcement. It varies depending on the district, but for the majority of off-grid camping sites there is a 14-day limit; however, interpretations of this rule vary. BLM specifies that, after 14 days, a camper must move outside of a 25-mile radius of the last campsite — USFS is more varied and unclear.

Southard gives another reason though, as many ignore the 14-day limit while others don’t: safety. “High residential mobility is a survival strategy pragmatically employed … to keep their sleeping locations unpredictable, for reasons such as to deter would-be assailants from attacking them at night,” Southard explains, as multiple people she spoke to were women with children only recently having fled from domestic violence.

The streets are dangerous. In the woods you might have bears, but there are enough places to find shelter that you won’t have to worry.

Much of the impact these peoples have on the land is because of its lack of amenities that are generally expected when camping. A firepit, perhaps. A picnic table to prepare meals. A bathroom, of course. But when staying on USFS or BLM land, these accommodations are rare or nonexistent, which leads to environmental damages, particularly the accumulation of trash and waste.

“When people don’t move frequently enough, that leaves little opportunity for the land to heal and regrow. When visitors come out to the forest we want them to see the trees, the wildlife, the pristine water—not somebody’s trash,” Boehm elaborated.

To better understand the scale of impact, take the biannual cleanup the Rosenburg Police Department conducts along the South Umpqua Riverbed in Oregon. In 2017, a team of six people worked for four full days and removed about 10,500 pounds of debris from along the river. Trash included potted marijuana plants, syringes, road signs, bikes, shopping carts, and myriads of other garbage. Residents of the South Umpqua Riverbed were given advance notice of the cleanup operation.

Cleanups are not cheap either. The USFS in Colorado Springs estimated that it costs between $700 and $1,000 to clean up each individual non-recreational campsite which, depending on the area and amount of abandoned debris, can be a significant strain to agency budgets.

And it is not just trash accumulation that has park service employees worried. Violence, the starting of forest fires and illegal drug activity have all been documented on federal public lands, the latter exacerbated in recent years due to the opioid epidemic.

Homeless use of public lands is a bigger conversation in some states than others though, as the dispersion of federal land is not even, and neither is homelessness.

The highest percentage of federally owned land is in the Western states and Alaska — with Nevada being the highest at 80.1% federally owned. In contrast, only 0.3% of Connecticut and Iowa’s land is federal land, centering dialogues and disputes about usage and management to mainly out West.

In parallel, California had more than a quarter of the total national homelessness at approximately 162,000 homeless persons in January 2020 — according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). More than one-third of all documented homeless individuals are unsheltered, according to the same report; however, western states such as California, Oregon, Hawaii and Nevada, have the highest percentage of their homeless being unsheltered at over 50%.

So what is to be done? How can federal lands be better managed to help at-risk communities?

One idea was to create a permanent camp spot for them. This was tested in 1992 on USFS land about 130 miles south of Portland, Oregon, in Umpqua National Forest where a campsite known as Blodgett was created. It permanently housed up to 25 non-residential long-term campers with six campsites, two chemical toilets, job counseling, and food and gas access. This was a trial operation though, and the campground closed after a year of servicing around 100 people.

Another more recent idea is from a nonprofit in California. Noah’s Community Village, a nonprofit, is looking to lease BLM land in Redding, California to build long-term housing for local people suffering from homelessness. As of January 2020, the nonprofit was still starting the paperwork to lease the land.

The problems that unsheltered residents in outdoor spaces struggle with are no different than those of their urban counterparts — lack of social supports, hygienic resources, shelter, financial opportunities — and they become homeless for similar reasons of lack of affordable housing and savings.

Their limited options can trap them in a state of desperation, and for those out West, often the public lands are their only option for a safe place to stay. One person, Becky Blanton, who started out living nomadically by choice, ended up doing so out of necessity, and told Vice, “The streets are dangerous. In the woods you might have bears, but there are enough places to find shelter that you won’t have to worry.”

Gifford Pinchot, the first Chief of the Forest Service, declared that the purpose of the Forest Service is “to provide the greatest amount of good for the greatest amount of people in the long run.” Public lands are a unique facet of America, they belong to all of its citizens. But who are they ultimately servicing and how can we shape them to better support all communities?

The Forest Service motto, “Caring for the Land and Serving People,” remains aspirational. In its current formation — the influx of trash and unsheltered residence without help — there is still a lot of work to be done.