A documentary of the homeless in 1990s New York tried to bring attention to housing issues that still persist today.

By Andrew Fraieli

The Broken

On August 30, 2000 the documentary “Dark Days” was released.

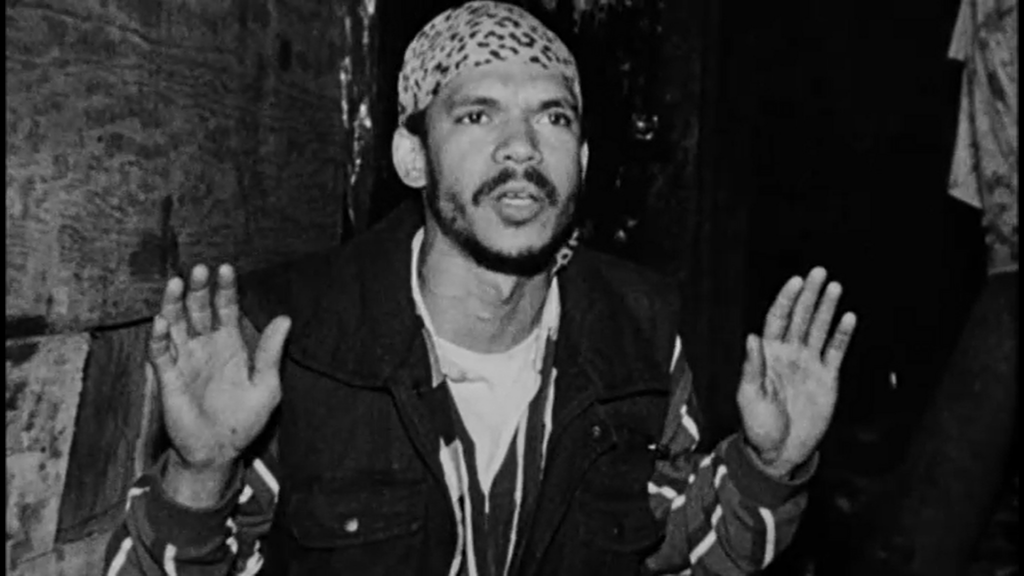

It begins with the bangs and whistles of an Amtrak train leaving the station, then flatly cuts to a man walking down a dark road. Jumping back to the piercing whistle of the train, we see a rounding tunnel view, then silence; the man is now in a park. The sound of the rattling train comes once again through a grate in a wall as it pans; the sounds echoing, the image changing to the same man — now with a flashlight — dropping into a narrow hole in the ground.

Darkness envelops and the camera follows him down a concrete slope to a flat-bottomed tunnel. Walking, we see a pile of wood, then another man, then a pile of wood with a door. Finally, we hear the first man speak.

“When I first came down into the tunnel, it looked dangerous, man. It was lookin’ real dangerous, ‘cause even in the daytime it was dark. And, like, I was scared. I said, ‘Somewhere down the line, it can’t be as bad as it is up top.’ Because out in the street, you had kids f**kin’ with you, you had the police f**kin’ with you, I mean, anybody can walk by you while you’re sleeping on a bench and bust you in the head. At least down in the tunnel you ain’t gotta worry about that, ‘cause ain’t nobody in their right mind gonna come down here.”

The tunnel he’s referencing is an abandoned subway tunnel under Riverside Park in Manhattan. It started to become a home for the homeless in the 1970s according to the New York Times archives — the people escaped harassment, the law, and the elements in this dark abandoned tunnel.

The film was created by Marc Singer who, at the time, had no filmmaking experience according to an interview with Indiewire in 2000. He befriended the people living down there and, using borrowed cameras, expired film, and volunteered time, started to film the problems these people faced to help draw attention to their troubles, and hopefully earn them some money.

The film premiered at the Sundance Festival in 2000, showing not just the harsh routine the homeless lived, but eventually the Amtrak police trying to kick them out from their only home.

About two thirds through the film, it transitions from their day-to-day struggle — like selling “nasty” books and collecting cans for cash — into this dilemma of being forced from homes they painstakingly built from scraps in a tunnel described by Singer in Indiewire as “…pitch black, rats running around everywhere, garbage, and smells that make your eyes water.”

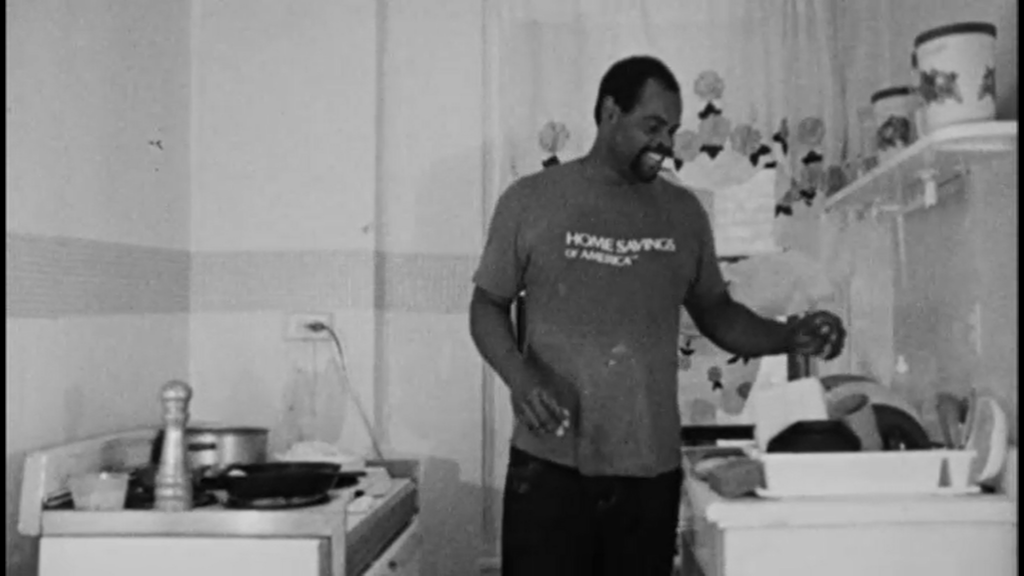

One man showers in a cold drip of water coming from a crack in the ceiling, while another goes off to feed dogs he keeps hidden away — shovelling the shit they leave behind and bringing them food to eat. Another man debates the difference between smoking weed and crack — a previous crack addict himself — trying to convince his newly accepted roommate to quit like he did and stick to marijuana.

Then, a still from the film describes an ultimatum, “In response to external pressures, armed Amtrak police are ordered into the tunnel to tell the residents that they have 30 days to pack up and evacuate or face a forcible eviction. Filming was prohibited.”

According to the residents, the police — armed with guns — came banging on doors and shouting orders to come out of their shelters.

“They said they wanted me to clean that shit up, I said I ain’t cleaning shit up. I got to move f**k I ain’t cleaning that shit up, you must be mad; take me to jail. That’s making their job much easier and shit,” said one of the homeless residents. “Last time, they was here during the winter, they said we had to leave. They said they were gonna do it in a humane way; we were gonna sit down at a table, gonna be some big wheels from Amtrak to discuss where we gonna go at.”

This, he says, did not happen, “Last time they was just here, they tell me they don’t give a f**k where we go. We just gotta go and shit.”

Shelters were a given solution to living in the tunnels, according to another man living underground, but they would rather be left alone down below.

“They said they were gonna try to get us housing or shelter or something else; I don’t know what that something else is,” says another resident. “I don’t wanna go to a shelter ‘cause I don’t wanna worry about them stealing my shit. They’re gonna steal all my clothes, they’re gonna steal everything I got. Drugs; it’s infected with drugs. What they should do is leave us down here. That’s what they should do.”

“We’re over here, down here by ourselves my friend, like family,” says yet another resident. “Man, you’re gunna break up the whole family. It’s not worth it man, it’s not fair to us.”

The Bandage

Switching to a daylight street, the film interviews Ben Harris at the Coalition for the Homeless in New York. He speaks on a previously won case defending the homeless from getting removed from Penn station by the Amtrak Police, and how the coalition wanted to go to court over the tunnel situation as well. This time they were able to meet with Amtrak officials before legal action.

“We met with Amtrak officials and they were, at first, very abrupt. They wanted everybody out. Had to be in a few days, they were gonna fence it off, put in security guards. And we worked out a plan that we would assist people into moving into temporary shelter if Amtrak would not evict people. But soon thereafter we learned of a program run by the federal government — a Section 8 program — and we guaranteed Amtrak that no one would be left inside of the tunnels,” says Harris.

The program he mentions is referenced in the film by a still of a New York Times article titled, “U.S. to Offer Housing Vouchers To Lure Homeless From the Subways”. It was started in 1994 after then Secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development Henry G. Cisneros toured the subway tunnels and witnessed the people who lived there. “One of the fellows could hardly speak for scratching his body and he described living with the rats and the lice,” Cisneros had said.

According to the same article, “Seven local nonprofit agencies will be given a total of 250 vouchers to distribute to the homeless,” with the program given a $9 million grant and transit police estimating that 1,500 may be living in the tunnels.

Harris continues on their use of the then new program, “The Section 8 program, the housing program here in New York City, is a great ticket into housing. It guarantees someone an apartment, helps pay the brokers and the security fees. So it was a perfect chance, and I think Amtrak knew that it’s a good opportunity to work with advocates rather than having a legal challenge. And on our part, on civil liberties’ part, we were pretty confident. Had we had to go to court, we would have won. It was a crystal-clear violation of people’s rights. But we didn’t want to defend people to live on the street. We wanted to get them into housing. That was the ultimate goal.”

And it was a goal they were able to meet.

The film fades one of their structures into view, different sized plywood nailed together, blankets covering holes, and one panel being pushed off from inside. A head pops out, “We’re outta here!”

The Coalition for the Homeless was able to get around 40 vouchers for the people living in the tunnels according to the New York Times article on the people living underground.

The scenes continue of sledge hammers smashing walls, and people packing. “It’s hard to believe it’s our last day in this place,” a resident says. “I thought this day would never come,” another responds. They were tasked with destroying their own shelters before leaving, and did so with the gusto of having a better place to go.

The film ends with the homeless who got vouchers explaining their plans in their new apartment, describing new furniture, jobs, and carpets, “It never will happen again. Ever, ever, ever. Never, never, ever happen. I will never go homeless again. That was like a nightmare. You know? And I woke up out of it, and I’m staying awake.”

But at the end of the same New York Times article from 1994 was a statement from then Executive Director of the Coalition for the Homeless Mary Brosnahan, “I’m afraid that every six months there’s some show that gets trotted out and people read about it and think something’s being done, but nothing really changes on the streets. If the same secretary who’s trying this bold move is willing to give us a hundred or a thousandfold this number of Section 8 vouchers, that will make a difference. But this demonstration program will not.”

The Possible

In 2019, 19 years after the film premiered and 24 since it was filmed, Brosnahan appears correct.

These people lived in the tunnel as a way to escape the prejudice of the above ground world. The world of public and police harassment, police harassment, and not being able to afford more than a park bench at night. These “tunnel people” may have gotten homes, and brought attention to the issues that were being shoved off, but their success hasn’t lasted through the years.

Fortunately, there are more options to solve those problems than before, even if they aren’t perfect. A concept being used today is called Housing First that prioritizes giving the homeless a home similar to the Section 8 program in the film.

Rudy Salinas, the Program Director of Housing Works LA, explains on “Adam Ruins Everything” that “with Housing First we prioritize putting people who experience chronic homelessness in their own permanent housing. Once we put a person in an apartment we are able to address all the issues and causes of why they became homeless in the first place.”

According to their website, 98% of people they house — generally chronically homeless people — stay housed. The idea exists in Florida as well, with research being done on its viability through yearly reports on the homeless population by the Central Florida Commission on Homelessness.

They define housing first in the report as “an approach to ending homelessness that centers on providing permanent housing first and then providing services such as mental health assistance as needed.”

It’s explained in the 2014 Florida Homelessness report — by the same commission — that 107 chronically homeless individuals were used as a sample in exploring the housing first concept. “Providing permanent supportive housing” for them they say, saves “a minimum of $21,014 per person per year, or $2,248,498 per year if the entire group were housed.”

They continue that even in a non-perfect situation money is saved: “Using Housing First and Permanent Supportive Housing models achieving a 90% Housing Retention Rate allowing for a 10% rate of recidivism, would still provide an annual community cost savings of $2,023,648.”

The Housing First solution is seen as a factually effective solution as well, according to the Florida Department of Children and Families Council on Homelessness report of 2017, “Housing first is recognized as an evidence-based best practice, is cost effective, and results in better outcomes as compared to other approaches.”

Many other approaches include a stipulation that they participate in programs to help health issues before they can get housing. According to the National Alliance to End Homelessness, “Housing First does not mandate participation in services either before obtaining housing or in order to retain housing.”

Housing First is not perfect, as Salinas describes while comparing strategies, “Seeing a person who’s been on the streets for dozens of years and expecting them to suddenly understand what rent looks like and how to turn the lights on is something quite different, it’s daunting.”

It was daunting, as well, to solve the problem of removing people from living in tunnels with all sides winning, but it happened. It wasn’t instantaneous and — comparing to today — it wasn’t a final solution either, but Housing First now exists in some form in 17 states.

As this solution, and others, continue as an option in today’s world, at least the dark days are already over for some.