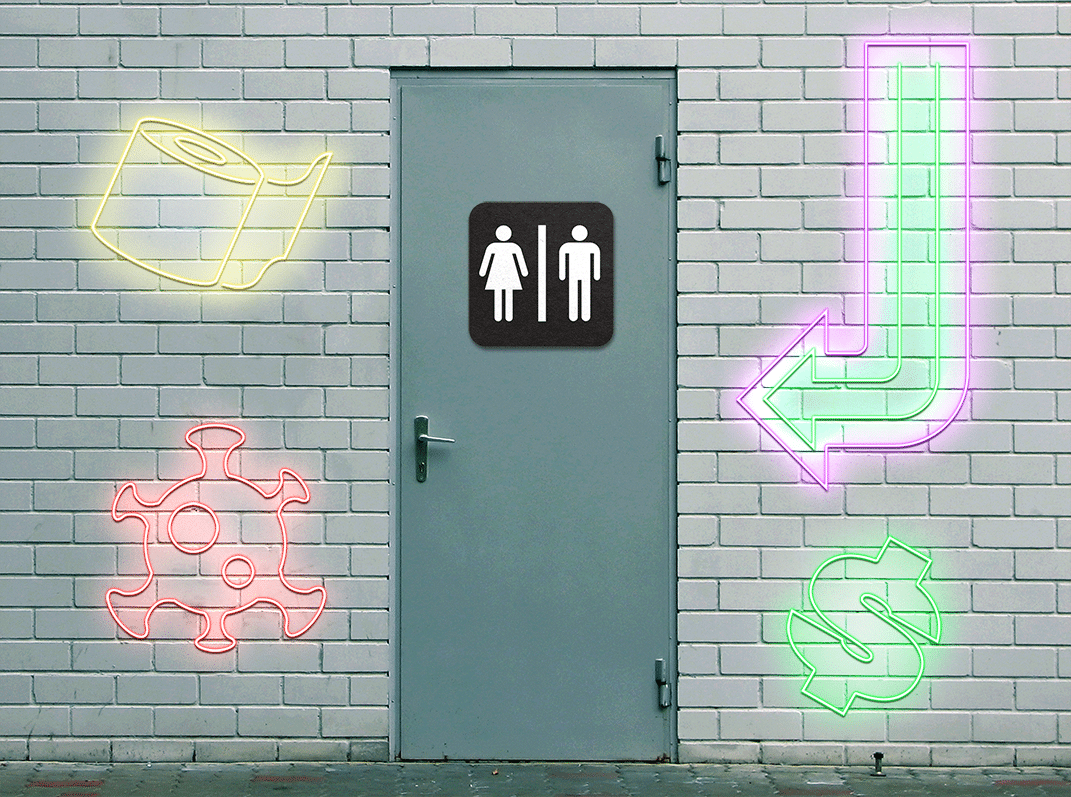

Public bathrooms are shrinking, or don’t exist at all. With private businesses filling the gap, where will the unhoused go?

By Andrew Fraieli

“Basically the street was the bathroom. That’s it.”

This is according to one man experiencing homelessness in Manhattan who goes by Derf. “When the pandemic started, nobody was trying to even let us walk into any store, at all. A lot of the McDonald’s were closed, the Wendy’s, the Burger Kings — they weren’t letting us try to use the bathrooms at all. It was horrible.”

Public restrooms and restrooms accessible to the public — like those in a Starbucks or McDonald’s — are not the same. Public bathrooms are designed for the entire public, but have been dwindling for years, slowly being taken over by these private businesses that are designed for customers, allowing the owners to charge and turn away whoever they desire.

Most often those being turned away are those experiencing homelessness, but they were already being refused before the pandemic too. Lockdowns and closures have simply exaggerated and shown to the general public what those living on the streets reckon with constantly: the almost complete lack of easy access to a restroom.

This privatization and lacking of public restrooms becomes a classist issue according to Taunya Lovell Banks, a professor at the University of Maryland School of Law. Private businesses can make decisions about who can come in, for what cost, and can easily discriminate in a way that a public bathroom could not.

“It’s a class issue, it’s a race issue, it’s a gender issue,” she said to PEW last year. And, “[during the pandemic,] middle-class white people who normally have greater access to toilets in public spaces are all of a sudden being denied access. Now they’re woke to it.”

New York’s own official tourist website tells of the snags the city has faced in improving public restroom access, mentioning how the city “contracted more than a decade ago to build 20 automatic public toilets” and how “most remain in a warehouse in Queens.”

The website does cite their park department’s website for public toilets in parks across the city, but also says that “sizable department stores, large-chain bookstores and restaurants offer restroom facilities for their customers,” highlighting private, customer-only, restrooms in the same breath as public ones.

A rally in Manhattan in 2018 highlighted this discrepancy, with City Council member Antonio Reynoso, according to the New York Daily News, calling for the mayor to have the remaining 15 automatic toilets installed. By then, they had been sitting in the warehouse for 12 years.

Where New York gives advice and lists some public restrooms though, as well as privatized ones, the city of Miami has almost none. This leaves private businesses as the most common, and in some places sole, place to find a restroom.

Many of these private businesses require a purchase before allowing someone to use the restroom. To the general public, this may be inconsequential, but it can be as much a barrier as a locked door to those living on the street who need every penny they have to survive.

Derf elaborates that no matter where the restroom is, and whether it’s public or private, they all have a cost anyways. Between the hours spent finding one and not earning money elsewhere, and the cost of transportation to get to the restroom, the price to enter a toilet is just another thrown on top.

This is assuming they are allowed into the business’ restroom at all. A Dunkin’ Donuts once told Mary Stewart, who has been experiencing homelessness for more than a decade in the Palm Beach area of Florida — and has previously written for the Homeless Voice — that they didn’t “want business from my kind of people.”

“If you can’t access a public restroom, and the businesses don’t want you going there…basically, if I had to go, I had no choice but to go in public,” Stewart continues.

David Peery, a lawyer who has experienced homelessness in Miami, a plaintiff from the Supreme Court case that created the Pottinger Agreement, and founder of the Miami Coalition to Advance Racial Equity (MCARE), says, in Miami, there’s a similar “uneasy tension.”

At Starbucks, “they know who’s homeless and who’s not. They give you that look when you come in, and give all types of reasons and excuses why they can’t give you that 4 or 5-digit pin code to actually get through the door and into that restroom,” he says. And at most McDonald’s he knows, they are “just openly hostile to the homeless coming in.”

The cost Derf speaks of, whether literal or consequential, as well as this classism and outright hostility of some businesses, forces many into the embarrassing and degrading situation of having to relieve themselves outside. And in places where this is illegal, according to Banks, “You’re criminalizing having a bladder.”

“…[during the pandemic,] middle-class white people who normally have greater access to toilets in public spaces are all of a sudden being denied access. Now they’re woke to it.”

New York, where public urination can be charged as a civil offense rather than a criminal one, issued 637 court summons for public urination in 2018. 2019 had 464, and by 2020 it fell to only 270 according to their online criminal and civil court summons reports.

Miami, on the other hand, has an ordinance stating that urination and defecation in public, unless by a child under 5 or by someone with a medical issue related to the bowels or the bladder, is punishable by a $500.00 fine, up to 60 days in jail, or both.

According to police reports supplied to the Homeless Voice by the Miami police department under a public records request, they arrested 12 people in 2018 for public urination, three in 2019, three in 2020, and seven in 2021 so far.

Other Florida cities have similar laws. Tampa, for example, has similar arrest rates as well, arresting one person in 2018 for public urination, eight in 2019, one in 2020 and one in 2021 so far.

Miami’s department of Resilience and Public Works told the Homeless Voice, though, that it had no comprehensive record of the public restrooms within the city.

According to Peery, this is because there are none.

The sole public restrooms are in the public library, he says, and inside the Government Center. Both of which are closed at night, and the library is closed on Sundays.

Perry references another public restroom that was built in late 2019 under the Metrorail station at Flagler Street and NW First Avenue for $300,000, but which has since been demolished. “Talk about fiscal responsibility and prudent use of public funds,” Peery says.

Stewart describes the public restroom issues in Boca Raton, where she’s currently experiencing homelessness, as more nuanced, saying the “access” to public restrooms has certainly decreased “because they started running homeless people out of the park.” She also “definitely haven’t noticed them building public restrooms.”

Whether it’s New York, Boca Raton, or Miami, people are being arrested for relieving themselves outside, and many of those people are experiencing homelessness and have no other choice. The need for public restrooms are not solely tied to helping people experiencing homelessness though, public bathrooms would help everyone. But often, homelessness is used as the excuse to remove or not even build them.

According to the Miami Herald, the Miami-Dade County Homeless Trust — the agency in charge of all funding, planning, and management of Miami’s priorities towards homelessness — is “philosophically opposed to building more public bathrooms.”

“The Trust’s leaders believe [public bathrooms] only encourage homeless people to stay on the streets rather than move to a shelter where they can receive a continuum of care, education, job training and financial support to make the transition to permanent housing,” they continue.

Ron Book, the Chairman of the Trust, which has a $65 million annual budget, told the Miami New Times, “Bathrooms and showers do nothing but sustain homelessness. It keeps folks out on the streets. It does nothing to end it.” He also elaborated to the Miami Herald that “bathrooms serve as a magnet for the [homeless] population to congregate and it becomes a burden on that area. You could try moving them away from businesses and condos, but where?”

In an op-ed in the Miami Herald in 2019, Peery directly responds to the Trust’s “philosophical opposition” saying, “I did not become homeless as a result of relieving myself in public facilities. And my own trips to the rare public bathrooms in downtown Miami certainly did not encourage me to remain homeless.”

Now, in 2021, Peery tells the Homeless Voice that the public restroom situation has “transgressed from ridiculous to dangerous.”

“[The Homeless Trust] has a policy of closing public restrooms and it has significant, concrete, public health implications to it. The failure to be able to wash your hands, control infections, during the height of the century’s worst pandemic? That’s outrageous. It’s dangerous, reckless.”

The Homeless Trust agreed to an interview, but did not communicate further prior to publication.

According to Peery, Miami’s “reluctant” response in early 2020 was to install about half a dozen port-o-potties for a period from April 2020 to late winter. He says the city did not maintain them, allowing feces to flow out of them for two to three weeks at a time.

“I used to think it was a matter of bureaucracy or incompetence, but after several years of dealing with this, I believe they know exactly what they are doing, these are intentional actions,” says Peery. “They are intentionally keeping these services off the streets in order to create these conditions, to justify their authoritarian actions that they take against the poor.”

“The Trust’s leaders believe [public bathrooms] only encourage homeless people to stay on the streets…”

To Derf, the idea of public bathrooms perpetuating homelessness is “a crock of shit.” He sees the issue being misled anxieties on improper usage of bathrooms — be it drugs, sex, or to sleep in. Derf agrees that these misuses happen, but that people like Book aren’t empathetic enough to care to figure it out.

Another argument, expressed by Book, is that those living on the streets want to stay there.

Stewart thinks there does need to be a pressure for those experiencing homeless to go to shelters, or find help to get a job and apartment, “but if you’re not providing adequate resources, not providing sufficient alternatives, than it’s only humane to allow homeless people to stay outside, to build restrooms for them.”

But to Peery, emphasizing the difference between urban homelessness and being in the woods, any excuse saying people living on the street want to live there is wholly ridiculous. “Why would anybody subject themselves to the theft, the violence, the intense trauma of urban homelessness? That’s intensely traumatizing, nobody chooses that. Absolutely no one, without question.”

He sees the argument as presenting those experiencing homelessness as the problem since it’s “their choice”, not the system’s fault.

“If you say that people choose to do something, then you can justify criminalizing laws and voluntary confinement and things like that,” says Peery. “If people are doing things involuntarily, then that requires you to look at structural issues and the systemic changes that need to be made. And they want to maintain the status quo, they don’t want to change the system. They’d rather blame the victims of the system.”

Public restrooms could, rather, solve many of the issues that are frequently complained about, by the city and the public, says Stewart.

“Adding public restrooms will not only be beneficial for the homeless, but will be beneficial for the public,” she says. “Littering, the sanitation, the poor hygiene, the public urination: the public restroom will be the solution to a lot of these issues.”

With this policy against public restrooms, they’re actually “creating the very conditions they complain about,” Peery says.

He hears city commissioners complain about trash, but not put more trash receptacles or sanitation services. According to Perry, they say those experiencing homelessness are “messing up life for us ‘normal tax-paying citizens’, but they’re the ones who actually created those conditions that they’re not only complaining about, but using to justify violating the civil rights of the homeless.”

These issues exist outside of Florida and New York as well.

The ACLU California released a report called “Outside The Law: The legal war against unhoused people” where they pointed out the same issue of how “local governments also withhold lifesaving services such as public restroom facilities and then criminalize unhoused people for necessary bodily functions like urination…”

And the North Carolina Law Review highlighted how dog parks and bags for disposing of dog waste are common, yet public restrooms are rare, saying, “The failure to provide bathrooms while prohibiting public urination and defecation is dehumanizing enough, but the prioritization of dogs over homeless individuals adds insult to injury.”

“Look at who the head of the homeless trust is, and where he comes from and who the Homeless Trust serves, they don’t serve the homeless, in fact, the Homeless trust doesn’t trust the homeless,” Peery continues. “They’re serving the business community, they’re serving the condo owners and residents, the corporate interests downtown, that’s who the constituency is.”

“There’s no sufficient alternatives to homelessness, there’s really not, and until there are sufficient alternatives, they need to allow people to camp out,” says Stewart. “They need to build things like public restrooms, allow homeless people to have access to toilets, running water, take a shower, wash up — because anything less than that is inhumane.”