In a state criminalizing homelessness at every level, some towns are trying to hinder giving out free food.

By Mary Stewart

Every day throughout the week people line up to be fed at Boca Helping Hands — many of whom are homeless. The first time I ate there a volunteer told me that I was in for a treat. I wouldn’t exactly call the quality of the food “a treat,” but I will admit that it was a halfway decent full course meal and a blessing for my rumbling stomach.

Back before COVID, Boca Helping Hands served sit-down meals in their dining area. Now, people have to line up on the sidewalks instead to receive their plates and eat elsewhere — usually in the nearby park. Those who have cars or homes pull up in their vehicles and receive their monthly food bags to take home with them.

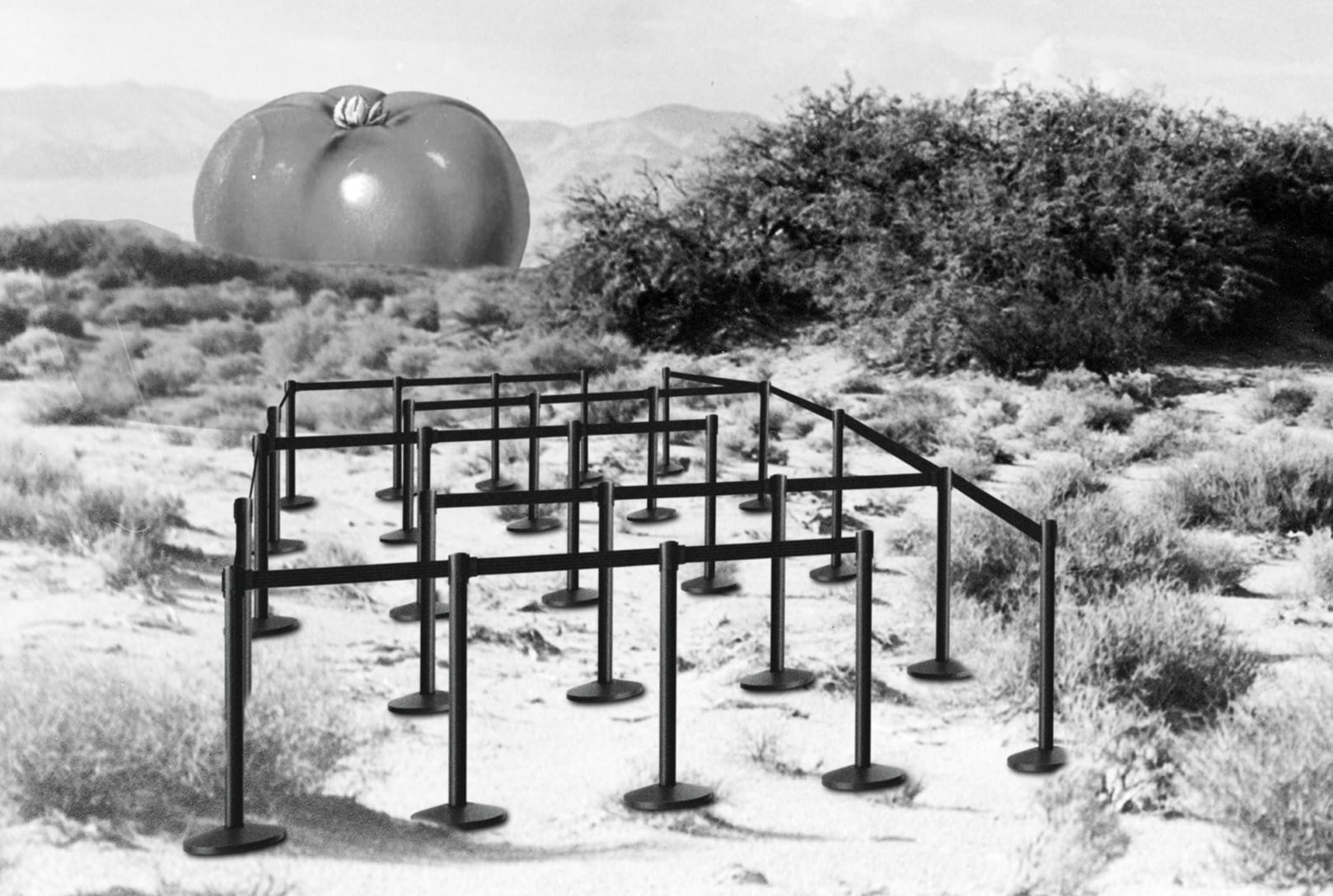

Some Florida cities, like Largo in Pinellas County, are aiming to hinder the ability of anyone to serve food or distribute any goods or services on public ground without a permit, which would include the sidewalk. Instead of outright calling the new law an anti-feeding ordinance, the county worded it as “regulating outdoor social service activities” as of its first reading in June.

Its supposed justification is that “the act of giving out free food draws large crowds and congests the public streets, sidewalks, walkways, and paths; threatens public safety; and damages public welfare.” But in my opinion, it’s just one more way to try to get rid of the homeless. Places would even be restricted to only two permits every 12 months, and would possibly have to pay for security, restrooms, and whatever else the town dictates would be required for safety reasons.

Most of the time, I panhandled to get money for food. I wasn’t a frequent guest of soup kitchens and outreach programs, but did find them to be helpful at times and consider them as much needed resources for the community.

For instance, when Palm Beach County had an ordinance against panhandling in the medians, there were many days where places, such as Boca Helping Hands, were my only source of food.

Even when I panhandled, I was very grateful whenever a good Samaritan bought me lunch or handed me leftovers or snacks. Sometimes I was given money, which was much needed as well. Then, I’d go eat out at Wendy’s or Chipotle and get other things I needed like my bus pass. But there were plenty of hard days where I was in desperate need of the food that was handed to me.

Anti-feeding laws take away these options for obtaining food. Without soup kitchens and outreach ministries, homeless people can either panhandle or dig through dumpsters for food.

But panhandling is also against the law in many jurisdictions, and some anti-feeding laws impose fines on individuals who give food to the needy.

In Sarasota, some homeless people know where the best dumpsters are and share that information with friends. The county doesn’t have any soup kitchens besides a day center and an outreach place that occasionally brings out meals.

I tried panhandling in that area until I found out that a cop threatened a fellow panhandler with a $300 fine. I heard that medians were off limits, and I didn’t make enough on the sidewalk for it to be worth the risk.

Admittedly, they do have the Salvation Army and U.S Housing and Urban Development apartments in Sarasota, but the waiting list for services is insanely long, and they don’t help out-of-county residents.

If we can’t panhandle, how do people expect us to eat without the help of soup kitchens and good Samaritans? But maybe that’s the whole point. Just watch the Discovery Channel and you’ll see that every living creature will leave an area where there’s not any food source and migrate to a place where food is plentiful.

“Homeless people who have income are often ineligible for food stamps.”

The real reason for anti-feeding ordinances is to encourage homeless people to go elsewhere — it has nothing to do with congested sidewalks.

Soup kitchens and feeding ministries can actually benefit communities as a whole and not only the homeless or low-income people they serve, they can lower the crime rate and reduce panhandling.

I still went out with my cardboard sign a lot instead of going to soup kitchens, but I know many many homeless people who eat at ministries on a daily basis, and I hardly ever see them panhandle.

My big issue was the fact that I had appointments and was actively looking for a job. Sometimes it was impossible to make it to the nearest ministry for lunch or dinner and still do what I needed to do that day.

I also figured out that it was over a two hour bus ride to get to Boca Helping Hands and back to my spot. It made more sense to just go panhandle for an hour and grab a Biggie Bag at Wendy’s.

Another barrier that some homeless people face is bus fare. They’d have to panhandle anyway to get bus money to go to the soup kitchen. They might as well just spend that money on lunch. But that doesn’t mean that we should shut soup kitchens down and stop serving the needs of our community.

Some people may argue that food stamps can meet the nutrition needs of the homeless, but the reality is that you can only buy cold foods that require preparation on Florida food stamps. Aside from a cold Publix sub, a bag of chips, and a soda, there’s not much that homeless people can buy on food stamps unless they have a grill.

Also, homeless people who have income are often ineligible for food stamps. Even if they don’t make enough to afford housing or their income isn’t steady, the state figures that they can spend their little bit of money on feeding themselves through the month. I know many homeless people who are on SSI or work day labor and have been turned down for food stamps.

One way around that is if people are over a certain age, otherwise they would receive limited benefits and have to participate in a work program. I think that’s fair except for the fact that homelessness is a major barrier to employment. It’s hard to get a job, and keep one, when you don’t even have a stable place to sleep.

With anti-feeding ordinances, limited to no food stamps, and outlawing panhandling, the only option that leaves us is dumpster diving. In addition to possibly making us sick, some business owners are strangely protective of their dumpsters. Once, I was chased away from a dumpster with a baseball bat — I was simply throwing away garbage.

The new anti-feeding laws remind me of the signs at the Tri-rail station that read, “Don’t feed the birds.” The theory is that if you don’t give the birds food, they’ll go away. But homeless people aren’t birds. We are human beings who deserve to eat without digging through a trash can.