U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development data shows African Americans as having a highly disproportionate rate of homelessness compared to their population since records began

Story by Andrew Fraieli

In 2014, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) found that “the sheltered homeless population that is Black or African American in the U.S. was nearly double the size of the full student enrollment in all of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) in the U.S., combined.” That is 604,317 homeless people compared to 294,316 students.

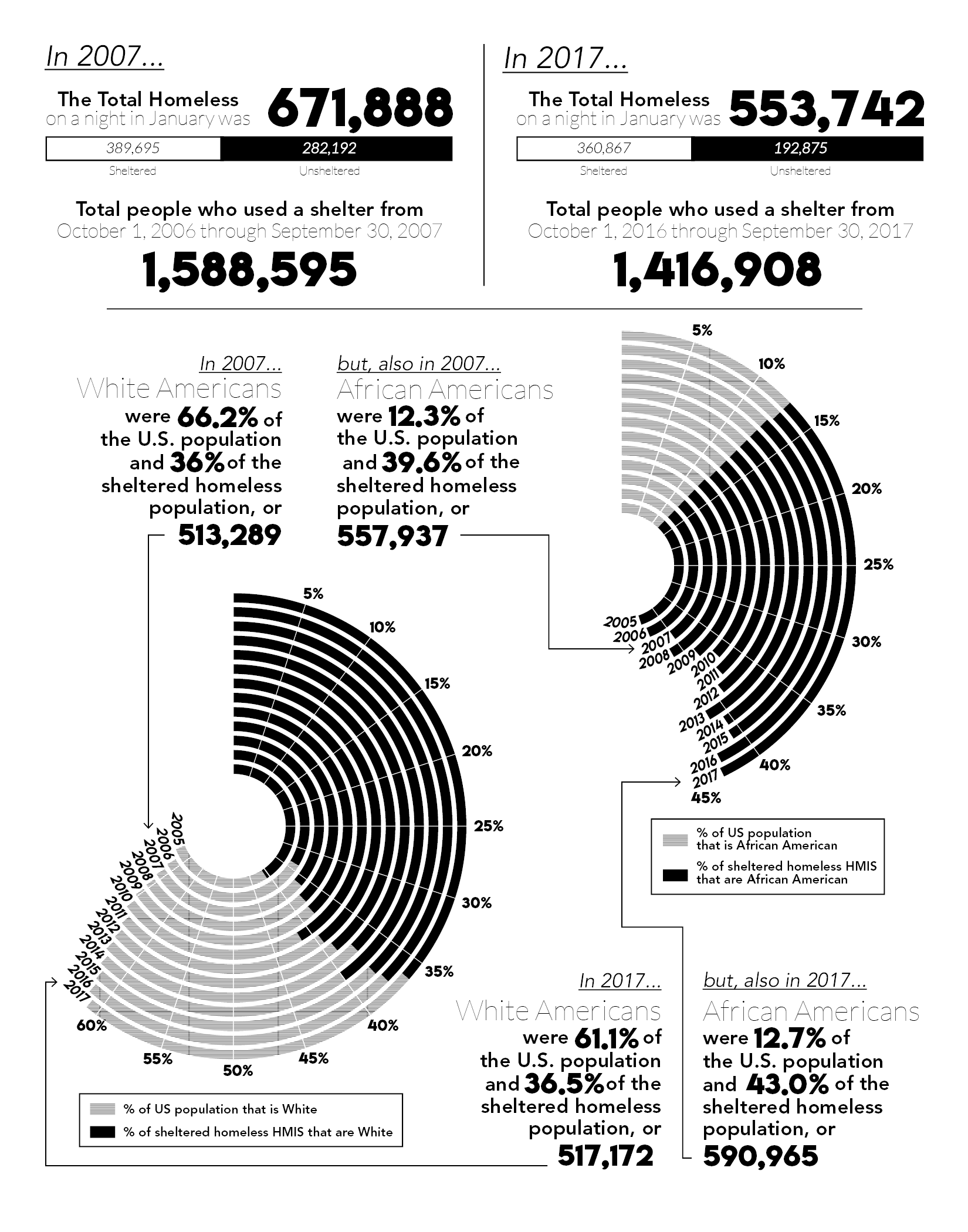

Since HUD’s Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) began, they have revealed the vast disproportion of homeless African Americans compared to their U.S population. Their third published report — and first to look at homelessness across an entire year — showed that African Americans, who are only 12.3 percent of the total U.S. population, make up 39.6 percent of all sheltered homeless people.

The HUD reports get information from various homeless shelters across the country and breaks it down in two main ways: the amount of people who used a shelter at some point in the year, and the amount of people who are homeless on a single night, usually in January. The latter is the point-in-time count (PIT), when volunteers at shelters go out and visually count the homeless they can find in their town or city.

“…the proportion and chances that any one homeless person is African American barely changes.

No matter what way HUD measures the number of homeless though, the proportion and chances that any one homeless person is African American barely changes. It is constant throughout their records since they started in 2007 that minorities are far more likely to be homeless, and African Americans are far more likely within them.

These proportions repeat, report after report.

The 2008 report states, “Homelessness disproportionately affects minorities, especially African Americans”; in 2011, “Minorities, especially African Americans, were significantly overrepresented in the sheltered homeless population…”; in 2012, “African Americans are among the populations most vulnerable to fall into homelessness,” and that report even points out “there were 2.5 times as many African Americans that experienced homelessness than ever earned a Ph.D. (1 in 171).”

In 2013 “African Americans comprised 41.8 percent of the population using shelter programs, representing the largest single racial group in shelter programs,” and in 2014 the exact statement is used again, but at 40.6%.

All this data so far hasn’t even covered those in the PIT count as up until 2014, there was no demographic data for it. 2015 was the first year that it did, and it showed that 227,937 or 40.4% of the total unsheltered homeless count were African Americans, and about 610,161 African Americans used a shelter at some point in the year, a similar 41.1% of people.

In 2019 — the latest information from HUD — the AHAR states, “African Americans accounted for 40 percent [or 225,735] of all people experiencing homelessness in 2019 and 52 percent of people experiencing homelessness as members of families with children, despite being 13 percent of the U.S. population. In contrast, 48 percent of all people experiencing homelessness were white compared with 77 percent of the U.S. population.”

For 12 years, these reports have shown that African Americans are at the highest risk of becoming homeless, with a peak of 45% of all people in a shelter at some point in a year being African American, even though they consist of only 12.3% of the U.S population. Every report had some statement that, in some form, said they were “heavily” or “considerably” or “significantly overrepresented” in the homeless population. The complete statistics can be found at the end of the article.

HUD’s reports are made for congress to help inform policy changes. These reports have their own possible issues and inaccuracies, but are the main source of homeless statistics for the government and many other organizations that help the homeless. It is not the only report that analyzes rates of homelessness though, and some try to give reason to this disproportion in the rate of African American homelessness.

The 2019 Housing Not Handcuffs report by The National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty, a nonprofit organization of attorneys located in D.C that focuses on ending homelessness, highlights more specific issues like general housing problems and incarceration patterns.

Similar to HUD, seeing as they cite AHAR statistics, Housing Not Handcuffs states “among the homeless population, Black Americans consistently have the highest rate of homelessness in the country, highly disproportionate to their population.”

It continues by citing “housing cost burdens and eviction” as a contributing factor to “grossly disproportionate rates of homelessness among people of color,” saying that “once housing is lost, racist housing practices prevent people from becoming rehoused. It is thus unsurprising that there is a heavy overrepresentation of people of color in the homeless population.”

Continuing with examples of incarceration, the report quotes an academic report, Pervasive Poverty: How the Criminalization of Poverty Perpetuates Homelessness, “As annual funding for public housing plummeted from $27 billion in 1980 to $10 billion at the decade’s end, corrections funding surged from nearly $7 billion to $26.1 billion transforming the U.S. prison system into the primary provider of affordable housing and many of its jails into the largest homeless shelters in town.”

Housing Not Handcuffs describes the situation where a “boom in jail and prison populations…disproportionately experienced by poor communities of color” combines with how “disproportionate arrests of homeless people contribute to the problem of mass incarceration, the criminalization of poverty, and racial inequality” adding to the academic report’s conclusions.

The exact causes of this disparity aren’t necessarily known, and the perfect solution isn’t either, but different organizations are trying, like The National Alliance to End Homelessness and the The National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty. Whatever the cause, the trend has been going for 12 long years.